International and Domestic exchange

Yuka Ikeda

Study Abroad Experience at the University of Würzburg

I would like to report that I completed my one-month elective internship at the Department of Nuclear Medicine and Anesthesiology at the University of Würzburg from April 7 to May 2, 2025. In this article, I would like to talk about the lessons and experiences I gained during my time studying abroad, as well as the differences between the medical systems and clinical settings in Japan and Germany.

The University of Würzburg is a national university in Würzburg, Bavaria, Germany, and has a very long history, having been founded in 1402. Its official name is Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg. It is also the university where Dr. Roentgen, who took the world's first X-ray photograph and was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901, taught, and there are many historical exhibits and monuments scattered around the campus. It was a valuable opportunity for me to have the opportunity to study at a university with such a long history and tradition.

First, the first two weeks were spent in nuclear medicine. I had the impression that most of the patients who came to the outpatient clinic had thyroid disease, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and autoimmune diseases. During this training period, I observed the entire process of SPECT and scintigraphy tests, and was also present at the explanation of informed consent. Compared to Japan, I got the impression that German patients actively ask questions to doctors and are more likely to frankly try to resolve their anxieties and doubts. Although differences in cultural and linguistic backgrounds may also have an impact, I felt that a more substantial informed consent was achieved by having both sides exchange dialogue at roughly equal rates. Therefore, I felt that in order to make informed consent work effectively, it is necessary to support patients' understanding and independent decision-making through patient education. In addition, during the outpatient observation, I was able to carry out thyroid ultrasound and blood sampling under the supervision of a supervising doctor, and learn various procedures in a practical manner. In Japan, medical students have relatively limited opportunities to be directly involved in actual procedures, but I was very surprised to see that in Germany, a system has been established in which students are responsible for a series of clinical procedures, from blood sampling to securing IV lines. In addition, I observed a sentinel lymph node biopsy for a breast cancer patient and helped with the preparation of dyes. When I visited a ward where radiotherapy is performed, I was surprised at the strictness of the contamination prevention measures, such as lead plates being used as shielding walls, changing shoes and washing hands, and checking for contamination with a special machine. In addition, there were lectures on reading CT and MRI images and thyroid cancer, and I was able to experience a variety of practical training contents every day.

The last two weeks were spent in the Department of Anesthesiology. First, we had a brief 5-minute information exchange at a general conference every morning, and then we went directly to our operating rooms. Here, we were given the opportunity to practice a wide range of procedures that would not be possible in Japan, such as bag-valve mask ventilation, peripheral venous line placement, adult and pediatric laryngeal mask insertion, and even tracheal intubation and extubation. This was my first time studying abroad, and I was initially very nervous because there were many procedures I had never performed in Japan, but the German operating room had an invasion room dedicated to the induction of anesthesia, and this environment was a great support. In the invasion room, there was a system in place that allowed for ample time for lectures and procedures, so even if the students were confused about the procedures, they would not be rushed by the surgeons, and the risk of mental stress and human error was greatly reduced. I was deeply impressed by this system, which combines education with patient safety.

What was even more impressive was that when anesthesiologists greeted and explained things to patients, they always removed their masks, smiled, and engaged in jokes and everyday conversation to dispel their anxieties. This is in contrast to Japanese clinical settings, where wearing masks at all times in hospitals has become the norm since the COVID-19 pandemic. I learned that showing facial expressions makes patients feel at ease, which in turn makes for high-quality anesthesia. Therefore, through my anesthesiology training, I was keenly aware that both learning practical techniques and smooth communication with patients and colleagues at work make for high-quality medical care. In addition, my supervisor advised all staff working in the same workplace to "try to speak to others as much as possible, even if it's just a few words." By lowering the barriers between superiors and subordinates and being friendly, tensions between people can be eased, information can be shared more easily, and work can be done more smoothly and enjoyably. In Japan, it takes courage to casually exchange words with your superiors, but I realized that starting with casual greetings and small talk, increasing conversation and building trust can lead to good medical care. These experiences made me strongly desire to not only deepen my medical knowledge, but also to become a doctor who never forgets to value human relationships.

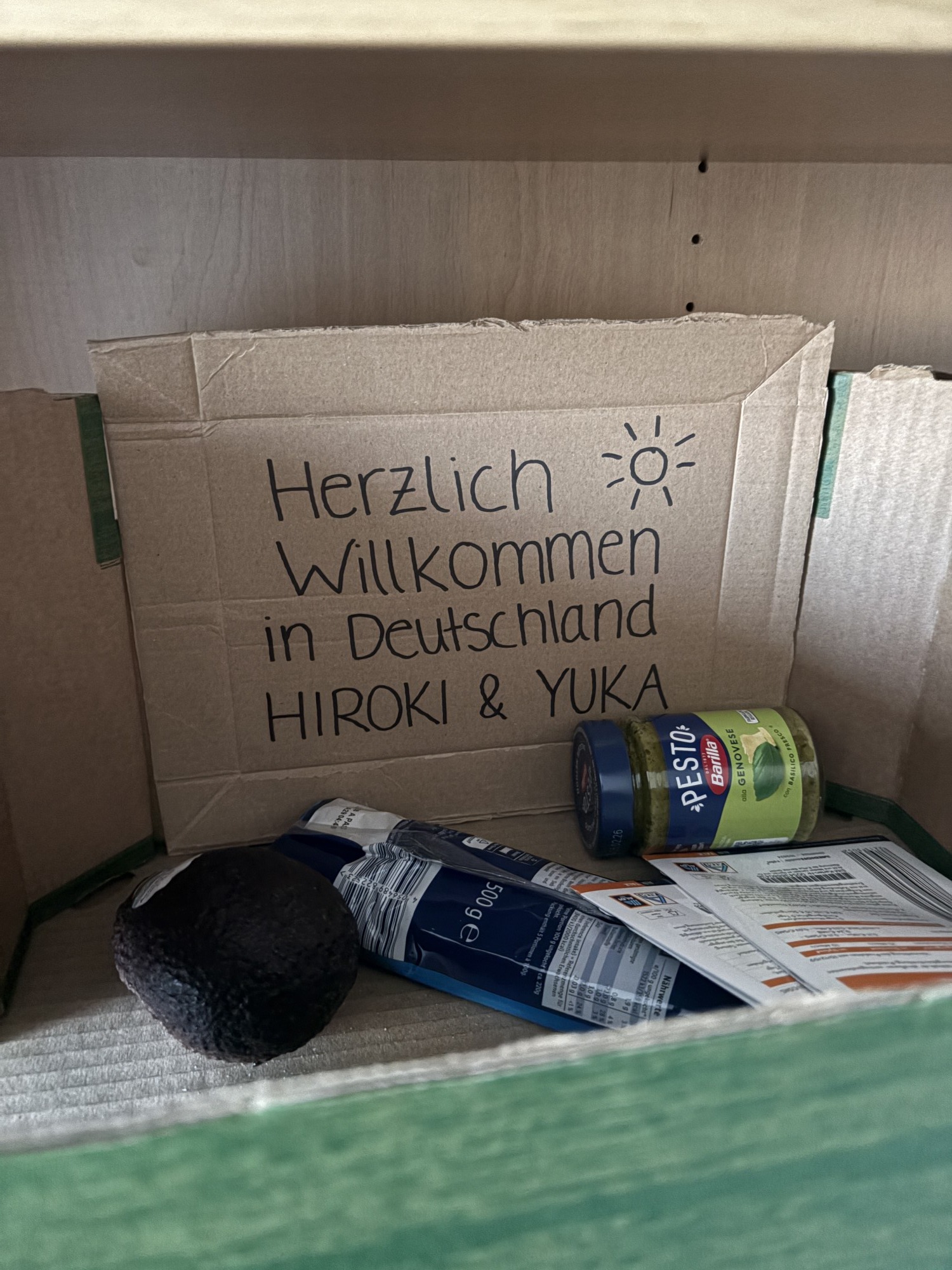

I had little interest in studying abroad until I was in my fifth year, but as graduation approached, I began to feel that I wanted to try something new while I was still a student. At that time, I happened to attend a study abroad program information session and heard the experiences of my seniors, and I was strongly attracted to the appeal of studying medicine abroad. I was never good at English, but I thought, "It's worth doing now because I'm not good at it," so I started speaking English and started learning the language again from scratch. Also, as I interacted with and went out with the international students from Germany and the United States who were at the university, my motivation to study abroad, learn English, and study medicine increased. When I finally decided to study abroad, I was overcome with joy and anxiety at the same time. I had no experience studying abroad, and I was worried about whether I could study medicine at a hospital in Germany for a month. However, when I actually arrived, the teachers and students at Würzburg University welcomed me warmly, and my tension immediately disappeared. When I finished studying abroad, I truly felt that I was glad I went. Although it was only a short period of time, it was an invaluable experience for me to not only learn medical knowledge and techniques, but also to have the opportunity to interact with patients and medical professionals in a different culture.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the professors at the University of Würzburg who supervised me during this study abroad, the students who helped me during my time here, the staff and International Center staff who supported me, and everyone who was involved in this program. Thank you so much.