国際・国内交流

原 マイケルシャノンさん(第6学年次)

“It starts with YES!”

私はシアトルタコマ空港に降り立ち最初に目にした広告に明るく大きな文字でそう書いてあった。目をキラキラさせ希望に満ちた子どもの下にはSeattle Children’s Hospitalとも書いてあり、“そう、俺はここで実習するために来たんや”と思い興奮が止まらなかった。私は5年生の学外臨床実習において、Washington University, Seattle children’s Hospital での海外臨床実習を選択させていただいた。多くの医学生は5年の終わりになれば、マッチングの準備や医師国家試験に向けて徐々に受験勉強を本格化させていく中、5年の2月というあえてこの時期に非常に貴重な1か月をアメリカでの留学生活に充てることはやや難しい決断であった。しかし、4年生では臨床統計の森本先生の授業で来日されたGeorge先生と交流を持たせていただいたことや、5年時には兵庫医科大学の先輩方や同級生だけでなく、他大学で知り合った同級生がアメリカに留学したことで、海外の医療、生活に非常に興味が沸き、この感情を抑えたままで残りの人生を送ることは大きな後悔を生むと考えたため、今回の決断に至った。

今回の実習はワシントン州のシアトルでありホームステイさせていただいた家は以前ワシントン大学の生命倫理研修で大変お世話になったDr. Stephen Kingのご自宅でステイさせていただいた。長女のCarys、双子のGenesisとGabrielの3人で楽しく一緒にボードゲームや映画鑑賞、庭でバスケットボールなどしてよく遊んだ。King夫妻はいつも私に優しく、まるで私が息子のようにかわいがってくださった。子どもたちは3人ともアイリッシュダンスを、長女と次男はクラリネット、双子の妹はハープを学校で習っていて毎日がアクティブで充実していた。私自身、中学から今現在もクラリネットを吹くため時には次男と一緒に練習もした。

ある週末はカナダへ一人旅をした。シアトルから観光バスで行くことができ、値段は往復60ドルとリーズナブル。バンクーバーで有名なStanley Parkをサイクリングしたり、夜はGastownを散歩し、翌日はVancouver Aquariumを訪れ充実した一時を過ごした。平日は実習が早く終わればDownton Seattleへ行きPike Place Marketで食べ歩きをしたり、Space NeedleやMuseum of Flightへ行ったりと一人観光を楽しんだ。アメリカのご飯はどこも量が多くとにかく美味い、一度ここで強調したい。

最初の1週間はワシントン大学病院でRadiologyを学び、残りの3週はSeattle Children’s Hospitalで小児科を実習させていただいた。Radiologyでは午前中に実際放射線科で働いている先生方の下につき読影の練習やケーススタディを行った。海外での臨床実習は初めてで慣れない医療英語を使うのにいつも必死だった。読影で日本語病名が頭に浮かんでも英語名が時に出てこず、全然違う病名を言ってしまい大恥をかいてしまったりもした。

2週目からいよいよ本命のSeattle Children’s Hospitalでの実習が始まり、私は総合内科で入院患者を診るチームに配属された。毎朝5時に起き、まだ外が暗く寒い中バスに乗り込み7時30分から実習が始まる。ちなみにせっかく持っていった母校の白衣は一度も着なかった(病院内で白衣を着ている人を一人も見なかった)。病院の建物にはそれぞれ Ocean, River, Mountain, Forest と愛称がついていて、内装もカラフルで子どもが親しみやすい工夫が隅々までされている。大体8 時にはレジデント・フェローは受け持ち患者についての状態把握を終えており、当直帯からの申し送りと回診前のミーティングに備えている。その後指導医とともに回診前のミーティングを短時間で済ませ、病棟回診へと向かう。

日本での回診の違いは、まず各患者さんへの回診の順番と時間があらかじめ決められていることである。順番と時間を決めておくことで、その時間に担当のスタッフや場合によっては医療通訳などを集めることが可能になる。また、回診は医師のみで行わず、看護師、薬剤師、栄養士一丸となり行う。病室の前で話し合う際は両親も参加し、チーム全体で親のご意向を傾聴する。このようなチーム構成は私がいた部署に限ったことではなく病院全体で行われており、数多くのスタッフを抱える米国だからこそ出来る事だという印象を受けた。

また、Seattle Children’sに来て驚いたのが、ほぼ毎日、何らかの症例検討会やカンファレンス、シミュレーションが院内のどこかで行われていたことである。昼の症例検討に関して運営はレジデントやフェローと比較的若手の先生が主導していた。内容も多岐にわたり、小児科のみならず関連する診療科の事、医療安全の事、医療倫理のことなど様々。聞きに来る先生も教える側のモチベーションも非常に高いため、良い循環が生まれる。毎週水曜はGrand Roundsという特別講義も大講義室で行われ、世界的に有名な研究者・臨床医が非常に興味深いレクチャーをしてくださる。演者は米国小児科学会会長など本当に豪華な方ばかりで内容も実に刺激的だった。

実習中、一番困ったのは薬剤・病名の発音の仕方だった。英語の病名やカタカナが頭の中に浮かんだとしても、いつも何気なく発音している関西弁のイントネーションでアクセントを置いても全く通じやしない。私の場合、自然な英会話が成立していたが医学英語になった途端そこで会話がフリーズしてしまった。”I’m sorry, I don’t know how to pronounce this properly”と正直に指導医へ伝え、そこから私達のディスカッションがまた再開した。

アメリカのポリクリ生はとにかく凄い。実習で“担当患者”を当てられたら、学生自身が一人で問診、診察、カルテ記載、処方、病状のインフォームドコンセント、さらに薬剤部へコンサルテーションも全て行う。自分で論文やガイドラインをリサーチし治療方針を考え、それを指導医と相談し二人で最終決定する。一般的に日本では初期研修医が行う業務を全員淡々とそして確実にこなしていた。少なくとも私はここまでしたことがなかった。加えて、アメリカは多文化国家であり全員英語を話せるわけでは決してない。私が最も印象に残っているのは4年生の同期が担当のメキシコ人患者さんの回診へ行った時のことであった。彼はなんとご両親にお子様の現在の病状と今後の治療方針を全て堪能なスペイン語で丁寧に説明し、質問も真摯に答え、両親は状況を完璧に理解し最後はこの上ない感謝を彼に送っていた。

あまりの感動に私はその瞬間、目が点となり言葉を失った。実に全てが完璧だった。“半端ないって…そんなんできひんやん普通…”自分の無力さに悔しさを覚えると同時に、自分も負けてられないと、とてつもない向上心が芽生えた。

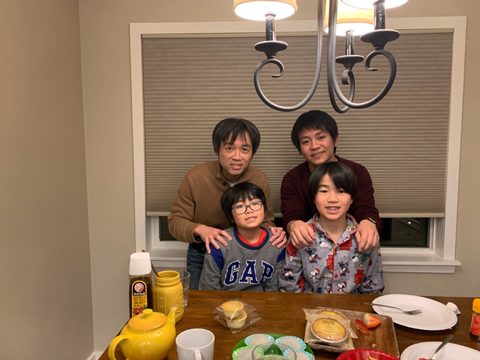

実習の後半に差し掛かり、私はある運命的な出会いをした。いつものように実習をしていると指導医から「そういえばマイケル、この病院に一人日本人いるけど会ってみる?」と唐突に言ってくださった。その方は当院のInfectious Diseases Departmentで働いていらっしゃってる大宜見先生という方であった。大宜見先生は日本の医学部を卒業し、USMLEを見事合格した後アメリカで臨床をされていてそんな方にここで出会えるとは思っていなかった。恐る恐るメールを送ってみるとその週末にはご自宅でディナーをお招きいただいた。久しぶりの日本食を頂きながら日本語で語り合い、本当に有意義な一晩であった。USMLEを合格している日本人の話を直接聞けることは自分の中では貴重でかけがえのないものだった。

悲しいことではあるが、あえてここで書かせてほしい。アメリカでは昨今Mental Healthが問題視されている。SNSなどといったSocial Mediaの普及による人間関係や学業のプレッシャーなど、現代の子どもたちはさまざまな不安を抱えそれに日々悩まされている。その結果、あまりの辛さに中には明日を生きる希望を失いIngestion(薬物などの過剰摂取による自殺)を図る。非常に心苦しいことではあったが、毎日一人は新入院となっていた。入院の翌朝話すと明るくて元気、素直で優しいTeenagerばかりなのになぜ…大学の実習でこのようなことは経験したことがなく、無垢な子どもたちというのもあり非常に胸が苦しかった。

この実習を通じて、漠然と小児科を目指していた想いが揺るぎない確信へと変わった。私はやっぱり小児科になりたい、罪のない世界中の子どもたちを助けたい、そう思いながら帰国した。あの時の学生のように堪能なスペイン語は話せないかもしれないが、少なくとも自分は英語が話せる。自分も絶対に負けてられない。日本の医師国家試験ももちろん、USMLEも視野に入れ、日本だけでなくアメリカでも臨床医を志したいと誓った。It starts with YES, そういう精神を肝に銘じて将来子どもを救いたい。

自由の国、アメリカ。“The land of the free and the home of the brave”(国歌 星条旗より)。後輩の皆、1ヶ月間英語しか通じない環境に一人で参加するのは不安かもしれないが、一人だからこそ色々自分で考え、時には自分を見つめ直し、そして行動するため、そこから学べることは多岐に渡り可能性は無限大である。また、そこでの出会いや経験はかけがいのないものである。是非来年、そして再来年、夢を持つ学生にこのプログラムに是非参加して頂きたいと願う。このようなチャンスは早々訪れない。It starts with YES, この言葉から始まる自分のかけがえのない思いをしてほしい。

最後にはなったが、ご尽力くださった野口学長、辻村先生、古瀬先生、お忙しい中ホームステイさせてくださったKing先生夫妻、長女のCarys、双子のGabrielとGenesis、Seattle Children’sの大宜見力先生、ご指導してくださったSarah Connell先生、Sarah Mahoney先生、Sarah Zaman先生、Lynda Ken先生、Michelle Gern先生、Jason Rubin先生、オリエンテーションでフレンドリーに日本語で話しかけてきた学生のBrandon Comish、Space Needleで知り合い仲良くなった日本人のYukaさん、書ききれないほど多くの方々にお世話になった。この場ではあるが厚く御礼を申し上げたい。