国際・国内交流

田中 和幸さん(第5学年次)

ワシントン大学研修を通して

8月3日から10日にかけて、兵庫医科大学5年生10名でアメリカのシアトルにあるワシントン大学で生命倫理の講義を受講しました。私はこのコースの存在を入学直後から知っており、当時から絶対に参加したいと考えていました。私はそれほど医学の研究に熱心な学生ではなく普段の試験もぎりぎり受かる程度の勉強しかできないのですが、海外の医学生、特にアメリカの医学生がどのような環境でどれほどの熱量で医学を学んでいるのかに興味があり、今回の研修に応募しました。今回の研修で私が特に気になった点について書きたいと思います。

まずアメリカの医学部の制度について、日本の医学部は高校卒業後、入学試験をパスすれば直接医学部に入学して6年間通った後、2年の初期研修と3年の後期研修を終えて一人前の医師になります。それに対してアメリカでは4年制大学を卒業した後、medical schoolに4年間通い卒業後3年間レジデントとして働いた後一人前の医師になります。どちらも11年間で医師を養成するプログラム構成になっていますがアメリカでは一般教養の学習が重視されているようで、必然的にアメリカの医師は医師免許だけでなく工学や人文科学などの学士も取得していることになります。アメリカの医学が世界でトップを譲らない理由は医師という特殊な職業の中にも様々なサブスペシャリティを持つという多様性が存在するからではないかと思いました。気になる学費については州立大学であるワシントン大学は州立大学ですが年間350万とかなり高額な学費になっています。しかしこの金額は州立大学の平均的な額だそうで、私立大学は年間600万円程度が平均だそうです。このような高額な学費であるにも関らず、ほとんどの学生は奨学金を借りて入学しているようで親が学費を出している家庭の方が少ないそうです。奨学金を借りてでも医学を学びたいという学生が多いというのも日本との違いかもしれません。

病院について、私達はSeattle Children’s HospitalとHarborview Medical Centerという2つの病院を見学しましたが、今回はSeattle Children’s Hospitalについて書こうと思います。Seattle Children’s Hospitalは名前の通り小児科専門の病院でワシントン州だけでなく隣接するアイダホ州、オレゴン州、モンタナ州とアラスカ州に住む重症疾患を抱えた子供への治療を提供しています。小児科だけで約650床という規模にも驚きますが、その全てが個室で各病室には患者の親が寝泊りするスペースも用意されています。また患者である子供たちが利用できるプレイルームや温水プールも用意されており、日本の病院の規模からは想像も出来ないような施設でした。医療制度の面でも経済的に高額な治療費を支払う能力がない子供が必要な治療を受けられるための病院からの補助があったり、遠方からやってきた両親に対する滞在に必要な情報提供を無償で行うなどの取り組みがなされています。いくら世界一の経済大国アメリカといえど、ここまで充実した環境を作り、維持していくための財源はどこから出ているのか不思議に思われる方もいらっしゃると思います。Seattle Children’s Hospitalがあるシアトルは有名なAmazonやMicrosoft、Starbucksといった世界最大規模の本社が集まっており、それらの企業からの莫大な寄付金がこの制度を可能にしているようで、エントランスの壁には病院に寄付した企業や個人の名前が書かれたボードが壁一面に貼り付けられています。ただそういった寄付を行っているのは大企業だけでなく、上述した温水プールは職員の寄付で増築され、プレイルームにはボランティアの方が常駐して子供の遊び相手をしているそうです。日本とアメリカではあまりにも環境が違うため、日本の医療にもっとボランティアを動員するべきだとは全く思いませんが、これからの医療を考える上で様々な国の医療現場を知り、良い点は積極的に日本にも導入していかなければならないと強く感じました。

最後に英会話について私が気付いたことについて書きたいと思います。私は人並みの英語力しか持っておらず、自信もありませんが、10日間でも日ごとに会話がスムーズになっていくことを実感できました。特に気をつけたのは自信なさげな様子を見せないという点です。旅行や留学で日本に来た外国人が流暢な日本語を話さなくても私達が気にならないように、アメリカ人にとって外国人である我々日本人が英語を流暢に話さなくても気になるはずがありません。むしろアメリカの方たちは論理構成に敏感であるように感じました。例えば君ならこの2つの治療のどちらを選択するか?という質問を投げかけられた時、つい両方の治療について長所と短所を述べて終わってしまいがちですが、そうすると「結局どちらの治療を選ぶのか?」といった具合に詰め寄られます。よく言われることですが海外の方と話す場合は最初に結論を伝えた方が喜ばれるようです。今回の研修を機に外国語を話している人も同じ人間で、気持ちを込めれば何でも伝わると実感することができました。

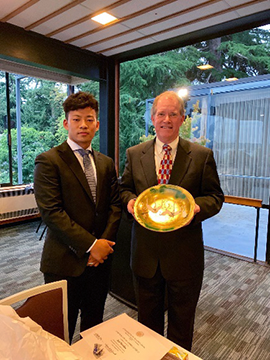

最後に、今回のワシントン大学夏期研修の機会を与えてくださった山西先生、引率してくださった枚方療育園の方々、蒲生先生、近藤先生、中村先生、講義をしてくださったMcCormick先生、King先生をはじめとする先生方、ありがとうございました。